Purpose and methods

what we do

Prairie dog research is a practice in patience, persistence, and timing. Every spring, John and his assistants arrive on site as the first prairie dogs are emerging from hibernation - or for non-hibernating species, well before the mating season starts. Sitting in towers or blinds over the colony, the team records behavioral interactions between dyads (two individuals) throughout the spring and into the summer. While John's research questions have evolved and changed over the years, he has consistently pursued questions on mating and breeding, infanticide and cannibalism, kinship and relatedness, dispersal and colony size, alarm calls and vocalizations, and the myriad hostile and friendly interactions that make up the social dynamics of a prairie dog colony.

Much of our work can be described as watching and recording, and our most important tools may be our binoculars and pens. But a day's work for the prairie dog squad is so much more, as maintaining a meticulous record of study subjects also requires extensive trapping and marking, collecting biological samples and fleas, and even conducting ultrasounds on pregnant females. Every morning we are in our towers before the dogs are awake, and we typically leave only after the last dog has gone to bed for the night. 10-13-hour consecutive days for four months brings us through early spring, the critical mating period, the nesting and weaning period, and the appearance of new offspring aboveground in the summer.

Research Questions

John's research questions have evolved throughout the years, are sometimes species-specific, and are always centered around the same foundation: the study of coloniality - its advantages, its disadvantages, and how coloniality manifests among different populations and across different species of the same genus: Cynomys. Some of John's recent research questions include:

- Why do females often mate with more than one male (described as polyandry) during the mating season, and how does polyandry affect mother and offspring survival?

- What are the proximate and ultimate drivers of infanticide, and what are the positive and negative consequences of infanticide for the killer and the victim mother?

- Why do certain species engage in communal nursing, by which females will sometimes nurse offspring of female relatives, and what are the benefits behind it?

- What are the evolutionary drivers behind alarm calling behaviors, especially when offspring are aboveground and females do most of the calling?

- How many offspring emerge after weaning as compared to how many fetuses were counted in utero during ultrasound procedures, and what can we infer about offspring survival from these numbers?

Methodology

Observation

The keystone of our behavioral ecology research is ethological (behavioral) observation. Recording hostile and friendly interactions between individuals reinforces what we know about the behavioral template of the species while providing new information during key life stages and events (i.e. the mating season, weaning period, and emergence of young). With these data, of which scores of pages are produced every season, John can continue to piece together the answers to long-standing research questions. Spending all day with the prairie dogs during critical periods of their lives allows us to collect an abundance of data across large sample sizes, assuring significance not only statistically but also ecologically.

Observation towers or blinds are positioned so that each observer is responsible for an area overlooking one or a few clans (family groups), with some overlap between observers in areas where density is higher. In this way, a squad of three or four research assistants is able to collect behavioral data on an entire subcolony of anywhere from 100 to 250 individuals (depending on population fluctuations) at our research site. The towers stand between 2 and 4 meters above the ground, so that we can live among the prairie dogs without disturbing them while we watch.

Livetrapping

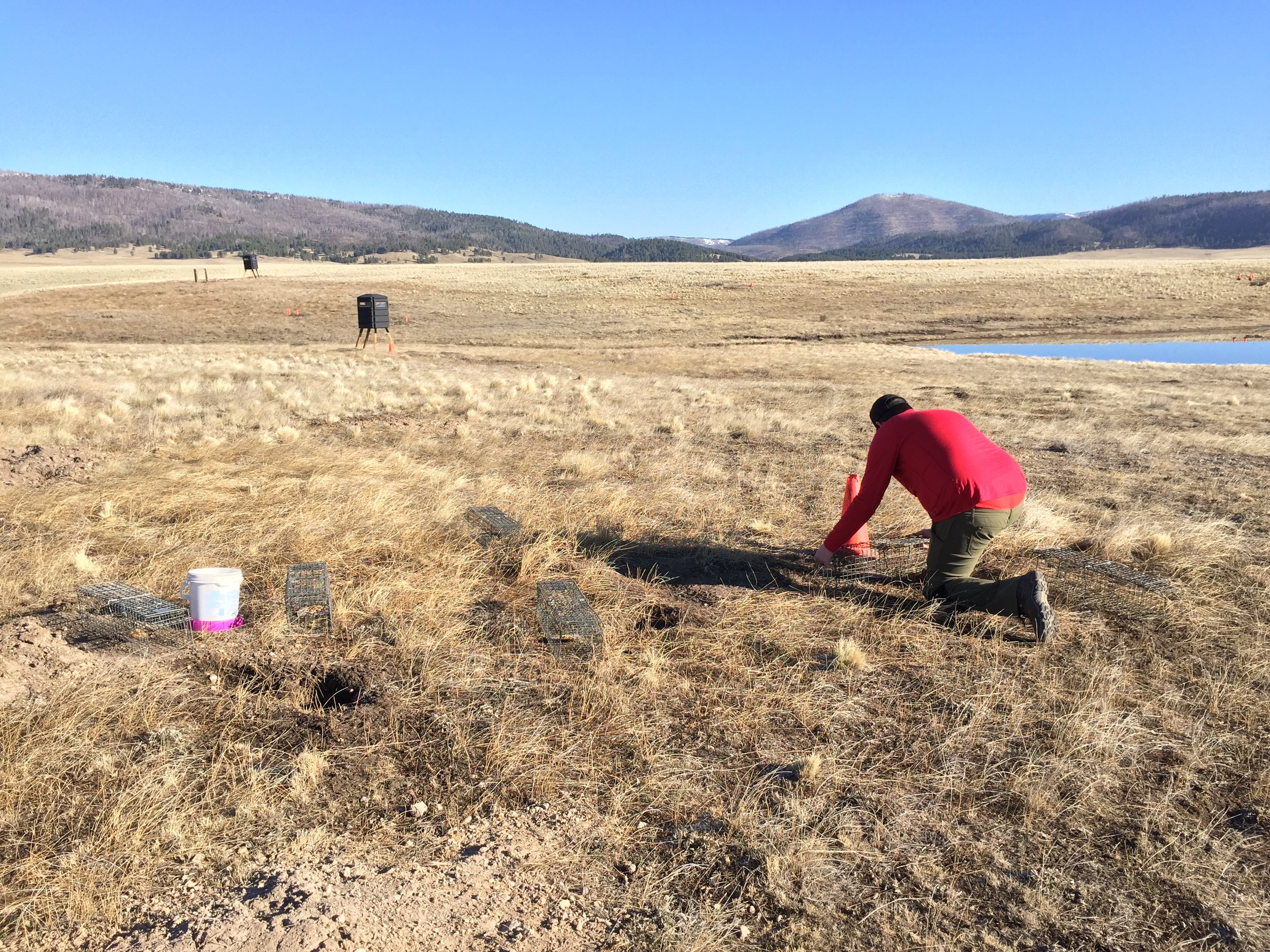

While a day in the life for our research team is mostly sitting in observation towers and taking data, we also spend a considerable amount of time jumping in and out of our towers to check traps. Every subject of our study must be captured and identified to enter the sample pool. Trapping enables us to give each prairie dog unique eartags as well as distinct markings dyed onto their fur for easy at-distance identification from our towers.

Prairie may be trap-shy as well as trap-happy, and it can sometimes be difficult to predict how easily any one dog will be to catch. We use Tomahawk live traps for all of our trapping: larger double-doors for adults and yearlings, and smaller single-doors for juveniles (babies). Choice of bait will often vary depending on the colony, but is typically a combination of oats and possibly sweet mash (which will generally be enough for a prairie dog’s interest), and if all else fails anything from bird seed to peanut butter to fruits and vegetables in the mix. Often, a trap simply needs to be out and open and a prairie dog may enter it without bait.

For general priority trapping (that is, prairie dogs we need to catch soon but not necessarily immediately), we will spread traps at varied distances around a burrow, bait the traps, and wait for our targets to get themselves caught. For high priority trapping (prairie dogs we must catch as immediately as possible) when spread traps aren't aggressive enough, we will surround a key burrow where the target is known to be, setting a wall of traps with no gaps entirely around the burrow, and temporarily plugging possible escape routes in the surrounding area with traffic cones stuffed in. We also use these special surroundings when catching litters upon first emergence, so that we do not lose track of the offspring and can ensure we are capturing every individual from the same nursery burrow and identifying them properly. Sometimes a crafty individual will jump over a surrounding, requiring an extra layer to make the wall higher. Sometimes both the front and back doors will be open to encourage shyer individuals. We start with a system and employ variations on a theme as needed.

Whatever the layout and situation, whether catching adults or babies, traps are always laid in multiples of 6, enabling easy accounting at the end of the day when traps must be empty, closed and inaccessible to either prairie dogs or other wildlife overnight. Trap inventory is done daily.

Handling

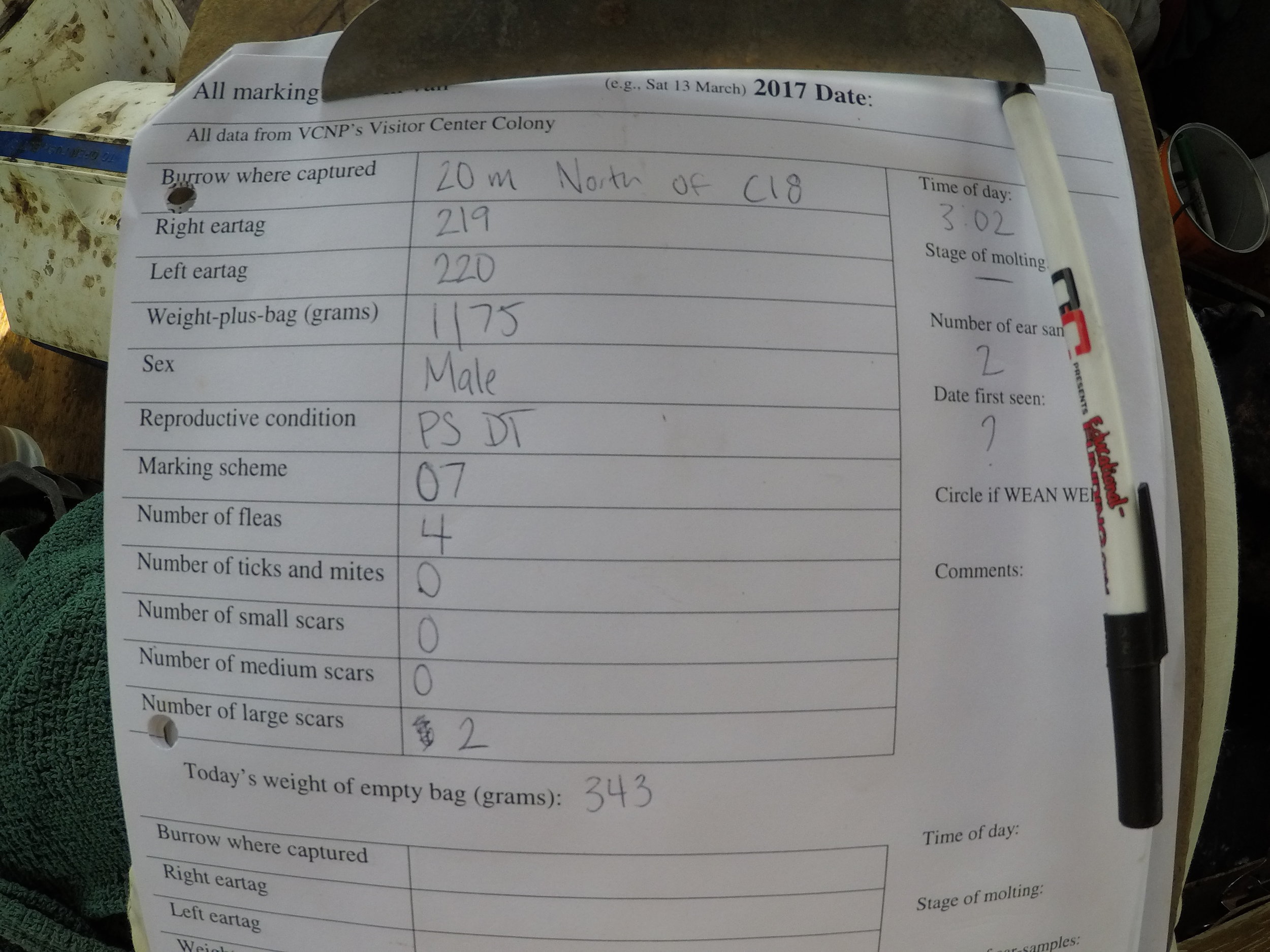

When a prairie dog is captured, the nearest field assistant will mark the trap with flagging tape and permanent marker, writing the burrow location where the prairie dog was caught and tying the flagging tape onto the trap. This step is a cardinal rule: every trap must be flagged before moving it, as the prairie dog must be returned to the exact burrow where it was captured so that we don't inadvertently cause the individual to become lost. Because of their high fidelity to certain areas in the colony, it is important not to displace prairie dogs, as the social and biological consequences can be dire.

After the trap is flagged, the captured prairie dog is taken either to shelter under a cart (if not being marked immediately) or straight to the marking van, where John and another research assistant are waiting to handle the animal.

During handling, the prairie dog is coaxed into a cloth handling bag. The handling bag enables easy access to the prairie dog’s body while keeping the animal and handler calm and secure. If the dog is a recapture, we check the eartags and its marking for identification. A weight is always taken, and sex and reproductive conditions are double checked. If the dog is new to the study, ear tissue is taken for DNA analysis, eartags are inserted, and a unique marking is assigned according to sex and age.

Marking

Marking schemes are specific. Females are dyed with a number from 50 onward or with a special marking such as wide apart bars across the flank (Wide Apart), a black butt, a back stripe, and others. Adult males are dyed with a number 0-49, and do not receive special markings. Yearling males all receive any number plus black dye on their rear legs to distinguish them from sexually mature males. Juveniles (babies emerging for their first year) are marked identical or similar to their mother and do not receive individual markings until the following year, with the only distinguishing mark being black ink on the head or tail for female juveniles. We use a product called Nyanzol dye, which is analogous to the hair dye humans use.

Through late May and early June, all prairie dogs in the colony will undergo a full molt, shedding their winter coat for a summer coat. Along with their coat also goes their dye marking. This means every prairie dog must be recaptured and re-marked with fresh dye, so that trapping and handling reaches a fever pitch at this time as known dogs are re-marked while newly emerging offspring are coming aboveground and needing to be marked. While the mating season may be the busiest time for behavioral data collection, this time in the summer is the busiest for trapping and handling.

A second molt occurs around late August through September of every year as the prairie dogs trade their summer coats for winter coats. While the spring/summer research has come to a close by that time, John does return to the research site every fall with a small team to complete what he calls a markathon, trapping and marking as many individuals as they can before winter, when prairie dogs will either dramatically decrease their time aboveground or, for hibernating species, descend into their burrows for the entirety of winter. Re-marking the dogs before winter ensures that our study subjects are easy to identify when we arrive for more research the following spring. While having to re-mark individuals multiple times with dye may prove labor-intensive, using Nyanzol dye has proven to be the least invasive method for easy identification from our observation towers. Other known methods for permanent marking, such as freeze-banding or tattooing, are more invasive, less visible, and often impractical for prairie dogs; while less permanent markers such as color-coded eartags and streamers are easily lost or torn out.

Ultrasounds

Gestation for prairie dogs is approximately 26-30 days, and for the last few years John has been capturing pregnant females at the tail-end of their gestation to conduct ultrasounds on them and take a census of fetuses in uteri. We time our capture of each pregnant mother precisely, needing to catch her when the fetuses are large enough to see clearly on the ultrasound, yet not so far along that the mother might give birth while we are trapping her. This gives us two or three days near the end of the gestation period to catch the enlarged mother, and our success varies every year but we have managed to catch enough pregnant females to have significant sample sizes for our ultrasound censuses.

The spine of one fetus and the skull of another. ©John Hoogland 2015

A clear spine. ©John Hoogland 2015

Prairie dogs have duplex uteri, wherein two uterine horns shaped like a V may contain many fetuses from the top of each horn to their junction. Because of this, it takes care and time to scan the entire abdomen with the ultrasound wand, and it takes multiple run-throughs to ensure we have an accurate count. Once we are satisfied that we know how many fetuses are in each horn (ex. 3 on the left, 3 on the right), John adds the count to a running list which we will later reference when juveniles emerge from their nursery burrows in June. By comparing fetus counts to final emergent-offspring counts, we can determine how many babies were lost per mother. Though we cannot say whether lost babies died before or after birth, or why they may have failed, we are looking to compare maternal behavior or other possible factors with offspring success.

©Marlin Dart 2017